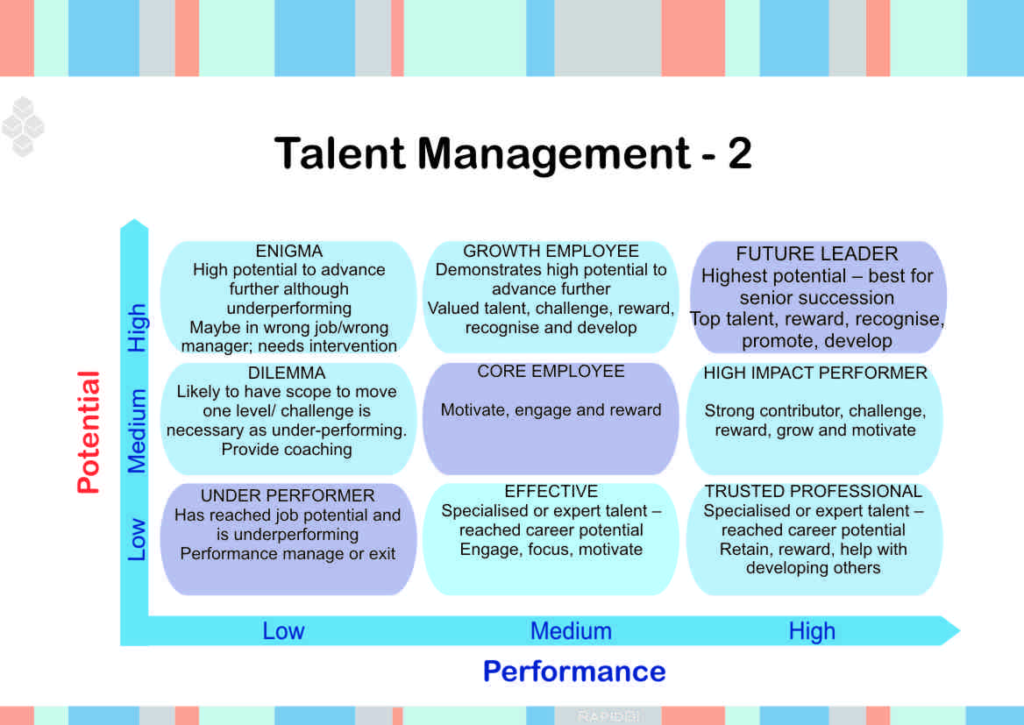

GE-McKinsey nine-box matrix

The 9 Box Matrix is a tool developed by McKinsey in the 1970s to help GE prioritize investments across its business units. It evaluates the units on industry attractiveness and competitive strength. In recent years, Human Resources teams have adopted the model as a talent management tool, replacing the two industry axes with performance and potential to categorize employees and determine which to promote, retain, and invest in, and which to reallocate. The HR version of the model is not standardized and there are variations in circulation.

I only figured out these secrets as early as 2015, where I’m not familiar of how calibrations were performed in those orgs at the time. So while I’ll share what worked for me, this is not a checklist of things that are guaranteed to make you successful.

The shift from technical efficiency to organizational restructuring

If your company has been in contact with a consulting company like McKinsey or Deloitte in order to reduce costs (read “improve efficiency”), you can sure bet that this model is being rolled out at your company. For some companies, there may be a theme of efficiency that started around 2018 with brainstorms of how to drive down cost mostly by improving data center efficiency. In the years that followed a Chief of Staff might have came in from one of these consulting companies and changed the way you looked at cost savings, at some point the 9-box model was likely introduced.

When we began to use this for calibrations, it also came with a suggestion that only 10% of the team should be in the “Future Leader” or Box 9. The general logic is that bonus should pay people for high performance and RSUs (e.g. with a 3-year vest) should compensate potential. The “Under Performer” or Box 1 also had a similar 10% guidance that aligns with the Vitality Curve created by Jack Welsh and misused since then.

This 9-box may have worked with GE as they prioritized their investments, but doesn’t fit to calibrate engineers, specifically because potential measurement in people is different than with capital expenditure investments. This adds noise to the process.

For example, these could be used to determine potential:

– “Next level” (e.g. at the levels higher than their current role) abilities and motivation

– Skills and mastery

– Ability to determine future target state

– Thinking beyond themself

– Automation

– Team player

– Learning

– Drive

Performance likely looks at:

– What they have worked on

– How they have done it

You may have heard the saying “pay for performance”, but that was more like “bonus and merit increase for performance, RSU for potential”. In some organizations, merit increases were essentially taken away from managers in favor of an HR algorithm that looked at role, level, and location and gave managers a value that was typically less than 3% unless someone was being promoted, then it was less than 9%.

The baseball card process with the McKinsey 9-box

Every organization is different, but some teams may be asked to pre-fill this 9 Box before calibrations.

During calibration meetings, managers presented a PowerPoint Slide that looks similar to a baseball card.

It might have sections like:

1. Box Number (e.g. Box 3 “Trusted Professional”)

2. Outcomes – things they worked on (notice I didn’t say completed work)

3. Skill dimension attributes like customer centricity, technical skill (design, quality, requirements, expertise, proficiency, efficiency), collaboration and an icon to indicate which level they performed at: developing, proficient, accomplished, and expert.

4. Basic details, like time in role (e.g. 5 months), level (e.g. E4, L5, MTS1), and date of last promotion

Shoehorn

Now we have two things: a 9-Box rubric and a PowerPoint slide for each person.

This step of shoehorning now attempts to assign each person a Box as engineering managers meet. Each manager, who doesn’t know much about other software engineers in other teams now needs to read an extreme summary of mutually exclusive information like “They worked on a database migration from Teradata to BigQuery” or “They are doing a great job as a scrum master”.

Given twelve different skill dimensions, and a baseball card summary, managers then decide how that related to being a “Core Employee” versus “Effective”. This is where much of the final decision rested on the manager’s ability to:

1. Present their case

2. Defend their case

3. Know what engineers worked on

4. Draw comparisons between other engineers

If someone is strong in their collaboration skills, but weak in their efficiency where does that put them? There are too many variables at play to be able to translate them into a single box. This is different than how GE may have used this by reviewing their portfolio of products to align on a box by compare revenue and growth estimates.

What can do you do as an employee? Humble brag about yourself, all the time, and keep a record of it. Record how significant your achievements are and make sure your manager, other managers, your skip-level, and other people know about them. Ask for a copy of the template your manager is using: fill it out for them. Use specific wording and highlight key achievements. You know the most about what you did, the goal of a calibration is for those achievements to be compared against others. Personally, I would want to control my own destiny as much as possible and over the years I’ve filled out my own promotion slides and calibration documents several times.

Rating all employees on one dimension at a time (in this example, safety) exemplifies a noise-reduction strategy we will discuss in more detail in the next chapter: structuring a complex judgment into several dimensions. Structuring is an attempt to limit the halo effect, which usually keeps the ratings of one individual on different dimensions within a small range. (Structuring, of course, works only if the ranking is done on each dimension separately, as in this example: ranking employees on an ill-defined, aggregate judgment of “work quality” would not reduce the halo effect.)

Kahneman, Daniel; Sibony, Olivier; Sunstein, Cass R.. Noise (pp. 293-294). Little, Brown and Company. Kindle Edition.

Ranking reduces both pattern noise and level noise. You are less likely to be inconsistent (and to create pattern noise) when you compare the performance of two members of your team than when you separately give each one a grade.

Kahneman, Daniel; Sibony, Olivier; Sunstein, Cass R.. Noise (p. 294). Little, Brown and Company. Kindle Edition.

How should it be done? Engineering Managers, here is my advice to you.

1. Reduce subjective skills that are assessed. Twelve different axes is too noisy. If this can be reduced to 5, then managers can provide an assessment of [Does Not Meet Expectations, Meets Expectations, Exceeds Some Expectations, Exceeds Most Expectations, Exceeds All Expectations and Beyond]. These scores should be transparent and specific for all of the 5 attributes and should be calibrated among all engineers.

2. Transparently weigh performance more heavily than potential, or remove it all together since most potential assessments in their current form are subjective. Use promotions as the time to look at potential at the next level using historical evidence, but use annual calibrations for salary/bonus/RSUs to consider performance.

3. Be more strict representing people. Move from PowerPoints to Documents with strict templates for sections, headers, length, and content. PowerPoint allows people to change font sizes, and change the sizes of sections: reduce noise by tightening the restrictions on managers. Add a total word requirement per section: Outcomes should be larger, subjective sections should be smaller. Give everyone a fixed amount of time to read the content for each person and also provide a fixed time for discussion for each person to keep calibrations efficient.

4. Look at some software engineering stats as directional, but not the only metric. Things like number of PRs opened, PR closure time, PR comments given may draw out outliers that will force a longer discussion if they are also in one of the top talent boxes. It may also force them down from the middle box if the justification is light. I have seen a few engineers where the number of commits dropped, their deploys dropped, and it triggered a discussion on productivity – as a manager, you need to be proactive here: don’t let this wait 6 months.

5. Have someone designated to check bias. “She was a rockstar and knocked everything out of the park” would likely bias others if a manager said that – and this kind of comment is subjective. A person who checks bias would stop this discussion from continuing. A less biased way to say that would be “She delivered all major milestones ahead of time with performance unlike anyone else within our team and at her level”.

6. Take notes. We would spend hours calibrating, but some managers would not keep their own notes. This creates a negative flywheel when they go back to the software engineer to discuss strength and growth areas. Feedback should be normalized during this process so that everyone receives it irrespective of their manager. This is different than promotions, where that process should, by default, collect decent feedback to folks seeking promotion.

7. Get rid of the 9-box. Come up with an anchor case, and rank engineers above or below that anchor case. Refer to rankings for each attribute as part of the calibration and determine how five different attributes will be averaged to create an overall rating. If your organization didn’t plan their budget effectively, and can’t manage the budget, and can’t be creative with solutions (okay, maybe not even creative, but humane) to avoid a layoff – use this ranked list, and a set of specific algorithms determined ahead of time, to determine where to eliminate roles. Key here: the 9-box system is noisy, especially for engineers: using this as your method for layoffs is a failure.

8. Don’t keep your performance management practices a secret. Everyone should know what specific actions are taken to determine top/mid/low performance. If you’re rating someone’s potential (don’t do this unless this can be objective), they should be getting consistent feedback on how they can increase that potential.

9. Practice, especially with new managers. Don’t do a single calibration. Create anonymized versions of each level and rating, then remove the rating and have managers rate them independently until you see a consistent final result. This has the side-effect of a more performant process as people get more task relevant maturity.

Goal Posts

This section deserves it’s own discussion as I’ve seen this happen numerous times over my 7 years as an EM.

Research suggests that a combination of improved rating formats and training of the raters can help achieve more consistency between raters in their use of the scale. At a minimum, performance rating scales must be anchored on descriptors that are sufficiently specific to be interpreted consistently.

Kahneman, Daniel; Sibony, Olivier; Sunstein, Cass R.. Noise (p. 297). Little, Brown and Company. Kindle Edition.

Here are some examples that have come up in calibration meetings:

- Not aspirational enough: Should a senior engineer who is delivering the most challenging projects, before deadlines, and helping raise everyone around them be penalized if they aren’t aspiring to be an even more senior software engineer?

- Critical project: Should someone who delivered a critical project be rewarded more than someone who delivered multiple projects during the same timeframe?

- Program Manager Software Engineering: Should a software engineer be rewarded for scheduling meetings with the team, and managing the backlog, but isn’t delivering any significant code?

- Responsiveness: Should someone who is responsive at all hours of the day and night be rewarded when they haven’t been able to deliver a project?

- Design over delivery: Should a senior engineer be rewarded for designing multiple systems and features when delivery of them has faltered?

- Delayed impact: Should someone be rewarded for designing a roadmap if that is for next year and unable to be proven out until then?

All of these questions should be answered with a sufficiently specific anchor, as Kahneman points out, for each level of performance.

For example, for a Senior Software Engineer, emphasis should be on both design and delivery of their projects. Equally weighted: where if the team is not delivering quality solutions fast enough, no amount of brilliant design will improve the rating. For Junior Software Engineers, design may not be as important, but consistent and quality delivery should be.

The key point here is that these discussions should not happen when you’re already in calibration sessions. Get together as a team and make sure you talk through these cases.

If there is an HR guideline (read: forced ranking) for who can be a top/mid/low performer, each person should be ranked against each other so that logical lines can be drawn at the respective cut-off points. What you don’t want to see are last minute attempts to figure out who to move into different buckets where goal posts get added just to justify a rating change.

Rewarding

One of the fundamental questions you should ask if you leadership team is: How are bonuses/RSUs/salary increases distributed? Does the VP make the decision or delegate budget to Sr. Director, Director, or Managers? If budget is distributed all the way down to each manager (ideally in a completely fair way, split equally), you could be missing out if you’re going the extra mile.

If budget is split among managers (instead of Directors or Senior Directors), this restricts the overall bonus that top talent can receive.

$1000 split between 5 managers allows each manager to give $200 as they see fit.

Taking that same model, but allowing for the $1000 to be pooled where 80% of that is given to 5 managers ($160 to distribute instead of $200), then leaves $200 to be distributed to top talent.

As a manager, I would prefer for the money to be pooled at the Senior Director level, with a fair calibration system, so that top talent can receive a larger bonus for going above and beyond. Unfortunately, at some companies, this is left up to the organization to determine on their own, so people are rewarded differently.

9-box for people or factories

Factories, like the ones General Electric used their 9-box for have physical machines and capital. Small changes to production lines, machinery, and formulas can improve performance. New equipment or future tech can improve the potential of that factory. Engineers aren’t the same as factories.

Engineers are curious learners, they can change their focus, improve systems, and deliver results. Communication is what helps engineers thrive. A failure of communication doesn’t mean engineers don’t have potential. A poor engineering manager may not create an environment where people are curious. Senior engineers may be overworked, stressed, and don’t give junior engineers something to aspire to: that doesn’t mean that junior engineer doesn’t have potential. Withholding opportunities for engineers to thrive is the fault on the potential of the leadership, not the engineer.

A manager who cannot accurately determine performance or potential introduces noise to the 9-box system. An industrial engineer assessing the performance and potential of a factory leverages a rubric with measurable criterium: you can’t say the same for performance reviews of software engineers. Don’t force-fit processes from one system to another because a consultant says it works. Don’t outsource your own brains to find the way to measure performance – if it doesn’t work at first, iterate – that’s what great engineers do.

FAQ

Why only engineers? I have the best knowledge of day-to-day engineering expectations, but I imagine a similar case could be made for Product Managers (PM), Program Managers (PgM), User Experience (UX), and Business Operations (BusOps).

If you remove the 9-box, what should be used? Only leverage your existing career ladder (for example, Square). Having two different frameworks creates overhead. As discussed in this article, slim down the amount of skills within that ladder to five or less.